The Push to Recognize Dustoff Crews

By Blair Drake

[2024 UPDATE: Vietnam Dustoff Crews to Receive Congressional Gold Medal]

During the Vietnam War, aeromedical evacuation units — commonly called by their radio call sign, "Dustoff" — and medevac units evacuated more than 900,000 casualties. Nearly 3,000 of those can be attributed to two MOAA members.

Lt. Col. Chris Siedor, USA (Ret), and Lt. Col. Steve Vermillion, USA (Ret), each served one year in Vietnam as Dustoff pilots. Both knew it was their calling.

"I entered the Army to be a Dustoff pilot," said Vermillion. "That was my objective. I had read an article and thought it was a cool mission profile to fly."

For Siedor, seeing a short video about Vietnam while attending college piqued his interest.

"The [video] showed a helicopter going across the sky, two wounded on the ground … and the camera flashes to the aircraft and it has a red cross on the nose. I was sold," he said.

Vermillion, then a warrant officer 1, arrived in Vietnam on Jan. 5, 1969, and was assigned to 45th Medical Company Air Ambulance (Dustoff). He recalls his first mission: "It was a hoist off of a tank. We were under fire, and …. the aircraft commander was training me. It was controlled chaos."

"

MOAA members can help by contacting their legislators and asking them to cosponsor legislation if it is introduced again.

'GET THE WOUNDED OUT'

Though Vermillion admits some of his missions still keep him awake at night, he describes his time in Vietnam as an "awesome experience."

"Those people we picked up, for each person we rescued … each one who survived went on to hopefully have a meaningful life and probably have two to three generations now under them," he said.

Vermillion left Vietnam in early 1970 as a chief warrant officer 2, having flown 1,145 combat hours and picked up 2,217 casualties.

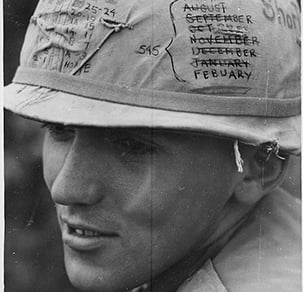

About a year and a half later, on Aug. 21, 1971, Siedor landed in Vietnam.

"The smell of rotting jungle hit me, and it was humid and hot," he recalled. The next day, he received his assignment to the 57th Medical Detachment, the original Dustoff unit. He was told: "No hesitation. No reservation. No compromise. You get the wounded out."

Not long after, U.S. ground combat forces left Vietnam. And a few months into his tour, "our helicopters were painted white to help protect us," Siedor said.

The danger soon grew. On March 30, 1972, the Easter Offensive began, bringing approximately 300,000 North Vietnamese Army soldiers into South Vietnam with their deadly anti-aircraft weapons. Siedor was serving in An Loc at that time.

In August 1972, Siedor's year in Vietnam came to an end. He had evacuated 719 casualties and flown 530 combat hours.

RECOGNITION FOR DUSTOFF CREWS

Though Vermillion's and Siedor's paths never crossed in Vietnam or during their subsequent Army careers, a common cause brought them together several years ago: a Congressional Gold Medal for Dustoff crews.

This effort has been underway since 2015, spearheaded by Medal of Honor recipient Maj. Gen. Pat Brady, USA (Ret), a fellow Vietnam Dustoff pilot. That year, Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) introduced a bill, The Dust Off Crews of Vietnam War Congressional Gold Medal Act. Unfortunately, the bill never moved out of committee.

In subsequent years, the bill has been reintroduced but with no progress. Vermillion and Siedor are continuing their efforts to educate legislators and find support for the bill in the 118th Congress.

"It defies belief that this bill continues to sit in Congress," Siedor said. "If you look at the statistics, it's clear why these crews are deserving," he said. "... They flew 24/7 and did not have the luxury of waiting for a cleared landing zone, the weather to clear, or night to end, as urgent patients faced death without immediate lifesaving care."

He and Vermillion, who is president of the Vietnam Dustoff Association, continue their work to rally support from veterans' organizations and contact legislators urging them to support this bill.

Both agree they want to see the crews and medics receive this award.

"I have said time and time again, this isn't about me," Vermillion said. "I look at my crew chiefs and medics and then I look at the family members of those who were lost … they deserve this honor."

Blair Drake is a contributing editor for MOAA who lives in Pennsylvania.