By Kipp Hanley

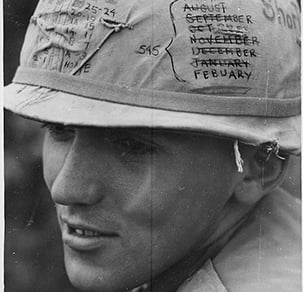

Army Sgt. Rick Duggan was nervous. The 20-year-old infantryman from the 1st Air Cavalry Division had just set up an ambush zone close to the demilitarized zone near North Vietnam when he was called back to the perimeter by his superiors. No one got called back unless something was wrong.

But instead of receiving bad news, the Manhattan native was handed a Pabst Blue Ribbon beer by John “Chickie” Donohue, his neighbor from the working-class neighborhood of Inwood. Seeing Donohue dressed in his madras shirt and white jeans so far from home was shocking.

“I just froze,” Duggan said. “I couldn’t believe I was seeing what I was seeing.”

"

These kids in my neighborhood were dying left and right ... I had to do something.

That surprise soon turned to a sense of fear.

Duggan’s superiors told him Donohue was his responsibility, so the two had to return to the ambush zone as darkness approached. That evening, Donohue hunkered down with the rest of Duggan’s outfit, at one point hugging a grenade launcher as a brief firefight ensued during the course of the night. Luckily, there were no American casualties, but Duggan knew Donohue had to get out of the area since his unit was leaving.

“I had to hitch a ride on the helicopter, assuming it was going to a place from there that was good for me,” said Donohue, who was working as a merchant mariner at the time. “… The closest place from there was Quan Tri airfield. … Anywhere south was good for me.”

MAKING GOOD ON HIS PROMISE

Donohue’s harrowing journey to Vietnam became known as “The Greatest Beer Run Ever,” and it has been captured in a book, documentary, and major motion picture. It all started after Donohue’s roommate, Bobby Pappas, had been shipped off to Vietnam. Donohue, who had served in the Marine Corps from 1958-64, was tossing back a few beers at Doc Fiddler’s pub one November night in 1967.

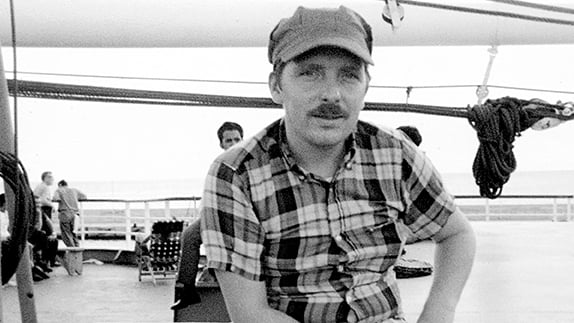

When the conversation turned to the war protests in Central Park, bartender George Lynch told patrons somebody ought to go to Vietnam to buy the American boys some beers. So, Donohue announced that he would do it, made a list of friends to see, and a few days later hopped aboard a merchant ship named Drake Victory carrying ammunition to Vietnam.

The boat needed an oiler, which Donohue was certified to do by the U.S. Coast Guard. He was confident he could make it to Vietnam, having traveled there before — ironically on a ship laden with American beer. But Donohue wasn’t so sure he could see all his friends he set out to see.

Tom Collins, the younger brother of one of Donohue’s friends, was serving as an Army police officer in Quy Nhon in the central highlands. Duggan was an infantryman stationed at the time in the Quang Tri province near North Vietnam, and Pappas was a radio operator at an ammunition depot just outside of Saigon.

“I didn’t think it was crazy,” Donohue said. “I thought it was possible — probably not probable, but possible. While these kids in my neighborhood were dying left and right and funeral masses were being held every few weeks, I had to do something. I was trained as a Marine, and a war was going on.”

FIRST ROUND

Collins was working as a bank teller in 1966 at age 20 when he was drafted.

After training at Fort Bragg, N.C., Collins, who was a specialist 4th class when he later got out of Vietnam, went to Quy Nhon, serving as a police officer in the 127th Military Police Company. He rotated his time between road and town patrols and assisting with convoys and POW camps. One day, he was on an ammunition boat on the Gulf of Tonkin when he saw on a tender a familiar face that he couldn’t believe was in Vietnam.

“I am looking at this guy, and I said, ‘I know this guy. Where do I know this guy from?’ ” Collins said. “Let’s face it, you’re not expecting someone from your neighborhood to show up. He comes along the side of the ship and says, ‘Collins’ little brother?’ And I said, ‘Chickie Donohue? What the hell are you doing here?’ He said, ‘I came to bring you a beer,’ and I said, ‘Holy s---, you are out of your mind.’ ”

Seeing a friend from the neighborhood in such an unexpected place was a pleasant surprise for Collins, who said that beer “went down like a glass of water.” After a few Pabsts and a night at a local bar, Donohue asked if he could take Collins to visit Duggan, an elementary and high school friend from the neighborhood who lived in the same building as Donohue’s family.

The story, which Donohue repeatedly used throughout the trip, was they had to go visit their brother and let him know about their recently deceased stepmother. Collins’ superiors weren’t having it, however.

“The first sergeant looks at Chickie Donohue, and looks at me, and looks at Chickie Donohue, and says, ‘I don’t know what the hell you’re up to, but Collins is going nowhere,’ ” said Collins, laughing.

SECOND ROUND

Before Donohue could meet Duggan, he accidentally ran into Kevin McLoone, a friend from Long Beach, N.Y.

Donohue was walking down the side of the road when he spotted his buddy driving a jeep toward An Khe, a town not far from where Donohue originally made port. A Marine who served in Vietnam from 1963-65, McLoone was helping the war effort as a civilian by installing scrambling systems in U.S. helicopters to make it difficult for the North Vietnamese to intercept radio frequencies the military was using.

McLoone stopped his jeep when he heard Donohue yell his name. He pulled over, downed a few beers on the side of the road, and then drove Donohue to a nearby air strip where he made his way north to see Duggan.

“He has a very distinctive voice,” said McLoone, who left the Marine Corps as a lance corporal. “I stopped the jeep and said, ‘What are you doing here?’ And he told me he was bringing beers [to his friends] to boost their morale.”

LAST CALL

After his sleepless night with Duggan, Donohue eventually sweet-talked his way down to Saigon.

Pappas was working for the Army Corps of Engineers as a civilian when he was drafted. He had received three draft deferments — the last one for his wedding day — before finally shipping off to Vietnam in the fall of 1967.

The newly married Pappas had just learned Donohue was in the country after getting a letter from Donohue’s girlfriend. However, he didn’t know all the hoops he had to jump through to see the rest of his buddies.

The two managed to share drinks on several occasions at the NCO club and officers’ club despite the start of the Tet Offensive, which was responsible for an explosion at Pappas’ ammunition depot. Luckily, Pappas survived, and Donohue eventually made it home safely in late March.

Ironically, Donohue had told Pappas during his going-away party that he would be over in Vietnam to have a drink with him at Christmastime. Turns out, he was off by only a month.

“I just thought, Yeah, sure,” said Pappas, who left the Army as a sergeant. “I didn’t know what he had done with the other guys, so I didn’t think it was any big deal.”

CURTAIN CALL

Today, the men are retired, living up and down the East Coast.

In September 2022, they came together to relive their magical moment at the Toronto Film Festival screening of “The Greatest Beer Run Ever.” After the movie, the lights went out and the spotlight shone on them, eliciting a five-minute standing ovation from the crowd. It was a far different reception than many Vietnam veterans had received after the war.

“They were never appreciated or apologized to for the treatment they received when they came home,” Donohue said. “I hope, if anything, [moviegoers] get that [I] appreciated what they did.”

Collins certainly did.

“There are not many Chickie Donohues around,” Collins said. “He could’ve stayed home, drank in the bar, and never put his foot in Vietnam, but he did. And that is something that I will always respect him for.”

Kipp Hanley is MOAA’s staff writer.