Note: This article is part of MOAA’s Transition Guide 2023, which first appeared in the December 2022 issue of Military Officer, a magazine available to all MOAA Premium and Life members. Learn more about the magazine here; learn more about joining MOAA here.

Negotiating is a skill that you can sharpen. And fine-tuning that skill can serve you well as you embark on a civilian career — whether you are negotiating on behalf of your employer or negotiating for yourself.

While negotiation may often seem like an art, the West Point Negotiation Project looks at the science behind the skill and teaches participants how to hone their abilities to negotiate. Lessons learned can be put to use during military service, but they can also help transitioning servicemembers succeed in the civilian workforce.

The impetus for the West Point Negotiation Project was to teach officers how to better communicate in complex situations during war and peace time. Launched by the U.S. Military Academy in 2009, the project provides a formal structure of negotiation for future Army officers. Those negotiations tactics are also now being taught as part of Civil Affairs training at Fort Bragg, N.C., and they are being implemented across the country in the academic and corporate worlds.

[RELATED: MOAA’s Transition and Career Center]

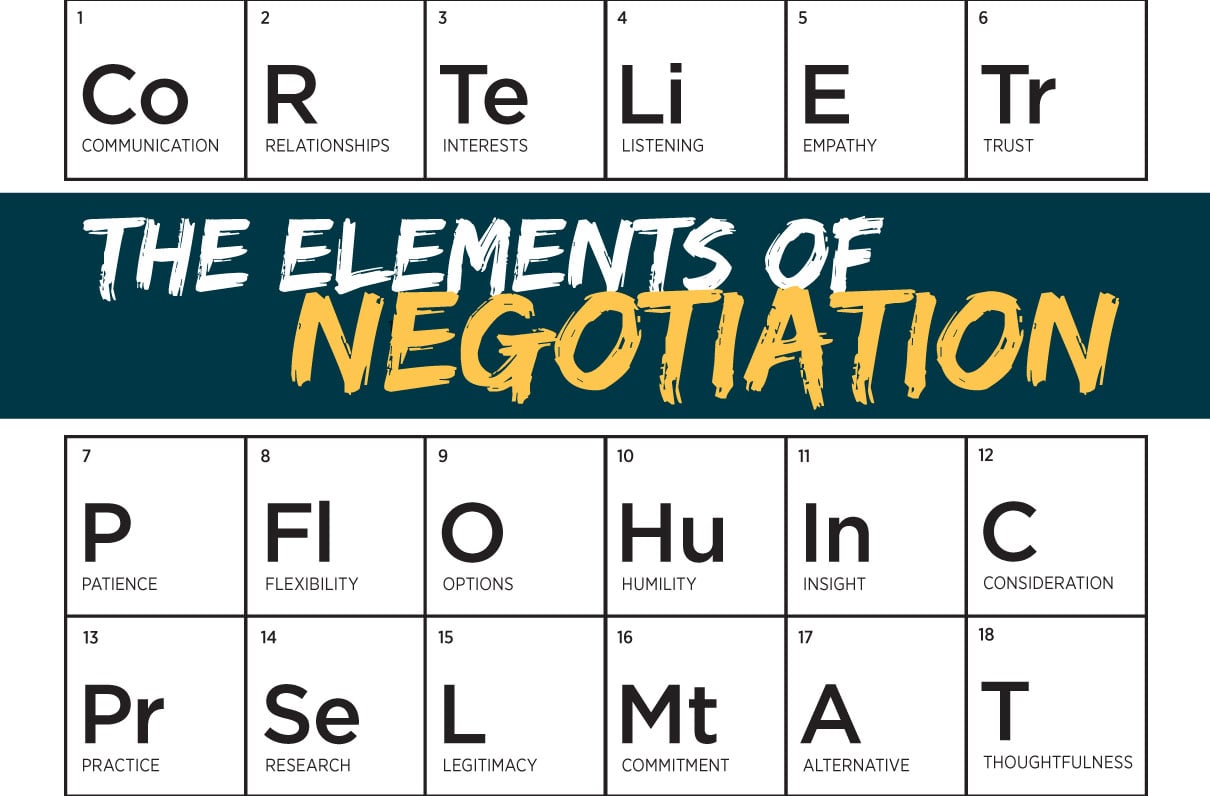

Here's a breakdown of the elements of the West Point Negotiation Project and how they can help you in your professional endeavors.

The Importance of Relationships

The project includes two classes, Military Leadership and Negotiations for Leaders. During the courses, West Point cadets are taught the seven elements of principled negotiations, created by late Harvard professor and author Roger Fisher: communication, relationship, interests, options, legitimacy, commitment, and alternative.

In the classes, cadets learn effective two-way communication. In order to do so, an individual must first establish a relationship with the other party. Whether it is someone you deal with on a frequent basis or someone you may never meet again, active listening and empathy are critical to the start of a successful negotiation.

“If you don’t trust the other side of the table, then you haven’t found the ability to build relationships,” said Maj. Travis Cyphers, USA, director of the West Point Negotiation Project.

Adam Silver, commissioner of the National Basketball Association, joins Gen. Martin Dempsey, USA (Ret), former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, on stage during a discussion with U.S. Military Academy students about the art of negotiation. (Photo by Delancey Pryor III/Pointer View/U.S. Military Academy)

Find Their Interests

Once you establish a relationship in a negotiation, then you can appeal to your party’s interest. Former Capt. James Oswald, USA, a 2012 West Point graduate, learned the hard way how not gauging your party’s interest can ruin a negotiation, even when you have already established a relationship.

As an investment advisor for Leading Edge Financial Planning, Oswald shared how his assumptions of a mentor ruined the chances of securing a potential client. Oswald and his colleague tried a hard-sell approach with an individual who had a sales background, instead of establishing what that person’s interest may have been. That approach backfired, and he never signed up.

“Our problem was he is not a client, he needs to be a client … instead of really asking him the right questions [like] what motivates him, what are his fears when it comes to finance, [are] there any gaps where he feels like he needs help,” Oswald said.

It’s also critical to know the distinction between the other party’s interest and position, said Maj. Tim Dwyer, USA, a former cadet who helped Cyphers write the negotiations curriculum for the Civil Affairs program at Fort Bragg.

To explain the distinction, Dwyer used a hypothetical example of an overseas partner force commander asking for new trucks. The acquisition of vehicles is his position, said Dwyer, but his interest is enhanced mobility. Instead of just denying his request, you might offer him the option of additional mechanical support or proposing cross-training mechanics in lieu of acquiring new vehicles. These options may be more legitimate or realistic than the purchase of new vehicles, said Dwyer.

[TRANSITION GUIDE 2023: Overcoming Culture Shock]

“Explaining that the trucks are old, but with the right parts and mechanical support, we can get them up and running for operations is a creative solution that gets to the underlying needs and wants of the partner force commander,” Dwyer said.

“Instead of getting caught up in the demand and position, we teach cadets the why behind it,” Cyphers said.

By exploring options in a negotiation, you may avoid making a commitment that may not be beneficial to you or your organization. For instance, when it comes to salary negotiations, do your research on the company and don’t jump at the first offer, said Cyphers.

The final element of negotiation is creating an alternative or BATNA (best alternative to a negotiated agreement). If you don’t establish the lowest threshold you are willing to accept, you can walk away from the bargaining table missing out on a potentially good deal or accept a deal that you shouldn’t be making.

“Cadets are often their own worst enemy in negotiations,” Cyphers said. “We limit the scope of what is possible before we enter negotiation.”

Growing the Program

Since its inception, more than 1,300 cadets have completed negotiation classes at West Point. In addition to the classes, West Point offers cadets and midshipmen workshops, which have featured well-known, successful business leaders, such as NBA Commissioner Adam Silver and former professional baseball agent and bestselling author Ron Shapiro.

The program also offers on-site instruction for officers in the field looking to improve their negotiation skills.

Capt. Jacob Caudle, USA, recently took the course at Fort Bragg as part of his Civil Affairs training and walked away with an appreciation of the formal structure of the class.

“People think they need to get X out of this meeting, and this is how I’ll go do it,” Caudle said. “There is more than just saying what … I want to get out of it. The relationship piece is crucial.”

[REGISTER TODAY: Upcoming Events From MOAA]

Outside of the military, the principles of the West Point Negotiation Project are being taught at academic institutions such as Dartmouth College. Formerly the director of Leadership Programs at the Air Force Academy, project co-founder Lt. Col. Aram Donigian, USA (Ret), teaches a negotiations class at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business.

Donigian always asks his students three questions: Who are you negotiating with, what are you negotiating over, and what makes those negotiations challenging? The answer to the third question is inevitably the same, said Donigian, and the elements of negotiations he teaches become applicable to all scenarios.

“Whether it is a cadet at West Point, whether it is a Navy SEAL, or any of the business contexts you can imagine, [the answer to the third question] is consistent[ly] the same because that [involves] people and organizational problems that you are negotiating,” Donigian said. “… There are limited resources, there are hard timelines, there’s costs when we don’t get [negotiations] right. People’s livelihoods, promotions, and performance reports are affected by what we do.”

Download Marketing Yourself for a Second Career

Newly updated! Learn what you can do to prepare yourself for a successful transition from military career to civilian career. This handbook shows you how to create an attention-getting resume, cover letter, and more. Get tips on self-marketing, job search, interviews, and interviewing. (Available to Premium and Life members)