Note: This article by Charlsy Panzino is part of MOAA’s Transition Guide 2023, which first appeared in the December 2022 issue of Military Officer, a magazine available to all MOAA Premium and Life members. Learn more about the magazine here; learn more about joining MOAA here.

Finding a new career can be a grueling process for anyone, but servicemembers transitioning to the civilian workforce may face unique obstacles.

Knowing what to expect during uniformed service can be more straightforward. In the civilian sector, however, transitioning servicemembers must learn how to network, articulate their value, and negotiate.

“Too often, servicemembers look at their military career as a pinnacle of success,” said Col. Brian Anderson, USAF (Ret), MOAA’s senior director of Career Transition and Member Services. “But that only prepared you to now go into your civilian career and find that next level of success.”

There are ways to help ease the transition and mitigate the culture shock some servicemembers feel as they start a new civilian career.

[RELATED: MOAA’s Transition and Career Center]

Top Tips for Adjusting

Networking. Connecting with others can help you find a job, but it also helps to hear about other veterans’ experiences so servicemembers aren’t blindsided when they make the transition to the civilian world.

When Cmdr. Erin Cardinal, USN (Ret), MOAA’s program director of Transition Services and Family Programs, asks servicemembers how they feel about networking, the response is usually that they feel uncomfortable or disingenuous.

Cardinal likes to share a quote about how networking should be thought of as farming instead of hunting: It’s about cultivating relationships, not just looking for something and leaving.

Even before leaving the military, servicemembers should share their story.

“Don’t make assumptions that family and friends know what you want to do or did do in the military,” she said.

[RELATED: MOAA on LinkedIn]

Translate your value. In the military, fellow servicemembers can get a clear picture of someone’s role just by knowing their duty title and rank.

“You’ve never had to worry about translating your value because it’s already part of the customs and the culture of what you’re doing,” Anderson said.

Many people in the civilian world won’t fully understand your skills, strengths, and accomplishments just based off those military details. Instead of listing military-specific duties on a résumé, Anderson said it’s important to know what to present to hiring managers and recruiters.

“What you did in the military is not as significant as how you did it,” he said. “And what are those things that you have, such as problem solving, decision making, whatever that may be, that really make you unique?”

“Civilianizing” your résumé, using language anyone can understand, is the first step.

[RELATED: Résumé Help From MOAA]

Project management, for example, can be talked about in a general way, whether it’s planning and organizing, delegation, teamwork, or leadership, said Capt. Pat Williams, USN (Ret), program director of MOAA’s Engagement and Transition Services.

“If I start talking about battalions or brigades or troop authorization, they’re going to be like, ‘What?’ ” Williams said. “Jettison all the jargon and speak plain language that any business person would understand.”

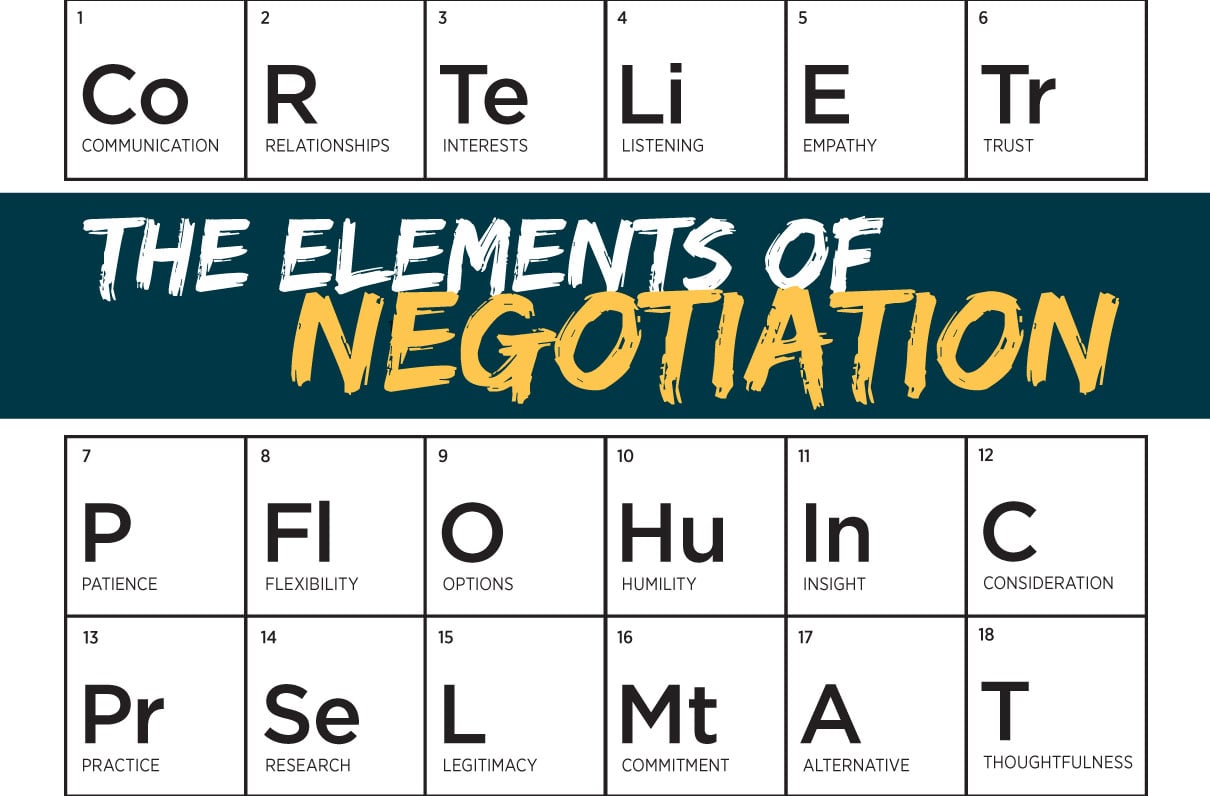

Negotiate. Negotiating your salary and benefits package is not something most servicemembers have needed to do. To become more familiar with the civilian sector process, transitioning servicemembers should do their research.

As you network and talk to veterans, ask what someone with the same knowledge, skills, experience, and education would be compensated at companies within that industry and sector, Anderson said. It’s also important to consider that overall compensation isn’t just about salary — take a good look at the benefits package to determine the true value of the offer.

Facing Challenges

Working in the civilian world brings unique challenges, whether it’s connecting with colleagues who don’t have that military knowledge or working for a younger boss.

Col. Wyn Elder, USAF (Ret), landed a job at Apple when he retired from the Air Force in 2016, but there were some bumps during the interview process he didn’t expect. Elder had served as the senior executive assistant to the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — a title that didn’t quite translate to the civilian world.

“I was interviewing with someone pretty senior at Apple, and he said, ‘Someone told me you had a pretty nice career, but were you a secretary?’ ” Elder said. “They don’t have job titles like that, so ‘administrative assistant’ is what he was thinking in his head.”

[RELATED: MOAA’s Job Board, Powered by Indeed]

Elder, who lives in Charlottesville, Va., and now works at Box, a cloud storage company, had mentors who gave him a heads-up about questions like that, along with advice on how to make the transition to a civilian career. There should be more training on articulating value to companies and translating experience into plain English to tell a story that aligns with what the business is trying to accomplish, he said.

Capt. Mary Jo Sweeney, USN (Ret), worked at USAA after retiring from the Navy in 2003, but it was still an adjustment learning how to demonstrate her business worth.

Sweeney, of Crownsville, Md., said she learned from other veterans and focused on “corporate literacy” by taking internal professional courses that helped her understand how USAA did business.

“And, most importantly, I listened a lot,” she said.

In addition to working with colleagues who don’t have military experience, finding yourself working for a younger boss can also be a surprise for veterans who are used to certain hierarchal structures, but breaking out of that mindset can be helpful.

[RELATED: MOAA’s Career Consulting Services]

Williams highlighted the benefit of reverse mentoring and getting rid of stereotypes to be more receptive to what someone else has to offer.

“It also speaks to your sense of belonging and your ability to assimilate into an organization,” she said.

A Two-Way Street

It’s important to make sure an employer is the best fit for you, even if that means not taking the first offer.

People don’t always spend enough time on themselves doing introspection, Anderson said. Questions to ask yourself include: What did I like doing? What working style did I like? If I could get paid for doing something, what would that be?

“Try to explore those opportunities and what they are, and then come up with what are your non-negotiables,” he said.

Also, don’t worry about asking for more, whether it’s a higher salary or another benefit.

“Don’t be afraid to advocate for your self-worth and the value proposition you bring to the workplace,” Cardinal said.

Charlsy Panzino is a writer based in Idaho.

Download Marketing Yourself for a Second Career

Newly updated! Learn what you can do to prepare yourself for a successful transition from military career to civilian career. This handbook shows you how to create an attention-getting resume, cover letter, and more. Get tips on self-marketing, job search, interviews, and interviewing. (Available to Premium and Life members)